Game Solvers

In [Introduction to AI] we defined Artificial Intelligence as rational goal-oriented behaviour exhibited by machines. We recommend you read that article first, if you have no prior expereince with AI. Throughout [Introduction to AI] we used the example of the chess engine as a case for a rational artificial agent. In this article we will explain how such unbeatable engines are made and show a concrete implementation for Connect Four AI.

This article is also (somewhat) available in a video form. So if you prefer a more visual explanation, you can watch the video here:

Brief History of Chess Solvers

Nowadays, chess is ruled by the machine. Openings are discrarded because of engines, theories are built on their evaluation. But that wasn't the case 20 or so years ago. For a very long time chess was taught as a game which requires great intellectual ability, possessed only by humans. It is because of this that early AI researchers focused on chess as a case study for developing robots.

The earliest example of chess engines was first built in the 1770s, by a Hungarian/Slovak engineer [1]. The Turk was able to play chess on a very high level, beating most of its opponents [1]. However, the machine turnt out to be a hoax. While indeed it was able to move around freely, the intelligence of playing chess came from a man hidden inside [1]. Thus intelligence was triumphantly reacquired back by humans.

200 years later, in 1981, Cray Blitz became the first chess engine to win a state tournament and also to achieve an ELO above 2200, becoming an officially recognised itnernational master [2]. Nearly 3 years prior, international master David Levy won his 1978 bet that no chess engine would be able to beat him in 10 years. Humanity's claim on intelligence was becoming contested.

1997 marks one of the most important events in AI history. In May of that year, Gary Kasparov, the then world champion in chess and one of the best chess players to have ever lived, lost to Deep Blue in a classical tournament (3.5 to 2.5). Something funny happened after their game. Kasparov, perhaps after some reflection or out of some spite for losing the game, accused the machine of “cheating”. To us nowadays this may seem absurd. We accuse humans of cheating by using AI solvers. But back then this was quite new. The machine had to be cheating by utilising human aid. Did DeepBlue cheat? To this day the debate is ongoing. Kasparov requested a rematch, but IBM turnt it down and disassembled the machine.

Now, 25 years after the infamous Deep Blue vs Kasparov match, engines dominate the rankings. Magnus Carlsen, the greatest chess player at present time, has achieved a peak rating of 2882, higher than any human in history. StockFish, the best chess engine out there, has a rating of above 3500. The two cannot even be compared.

Minimaxing your way to the top!

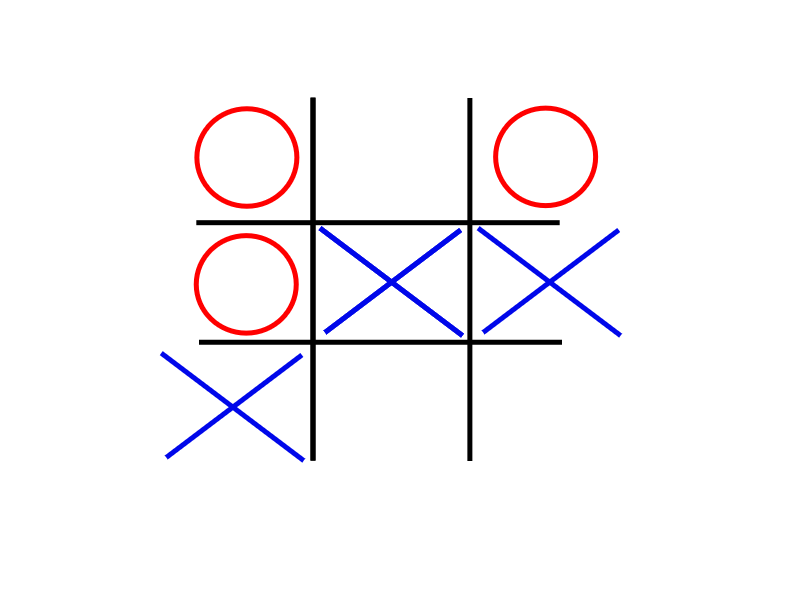

Most modern engines, be it chess, connect four, or many other such games, have the same innerworkings. They all make use of the MiniMax algorithm to evaluate which valid move to play next. Minimax is a special variant of backwards induction (if you are familiar with that one from your Economics classes). As the name suggests, we will analyse the game backwards. Lets consider an example - tic tac toe. A very simple game with quite a few possible positions, which makes it very easy to reason about without the help of any computers. Imagine you were playing with your friend, taking turns to put your Xs and Os until you have gotten to this position.

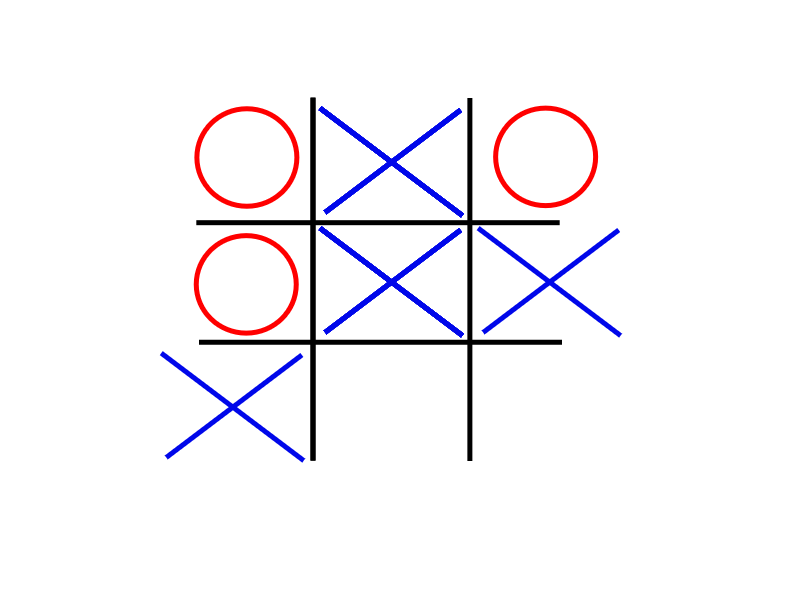

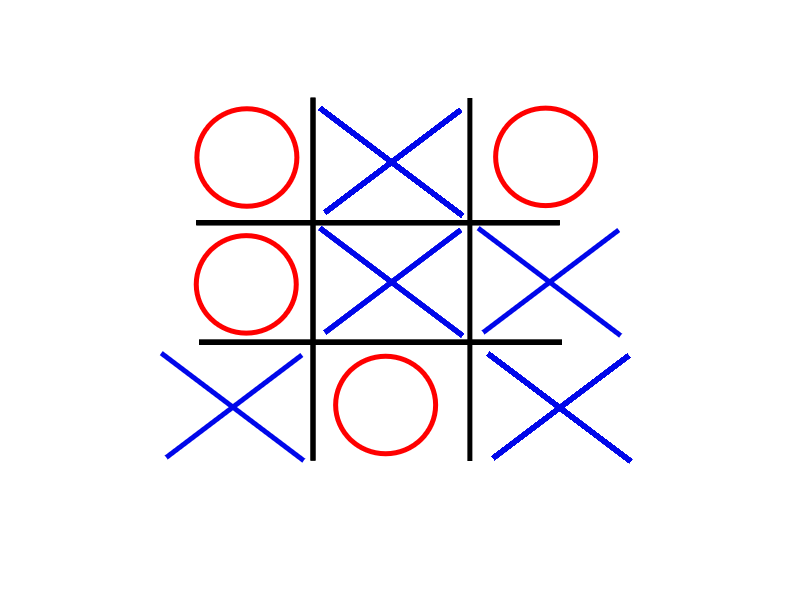

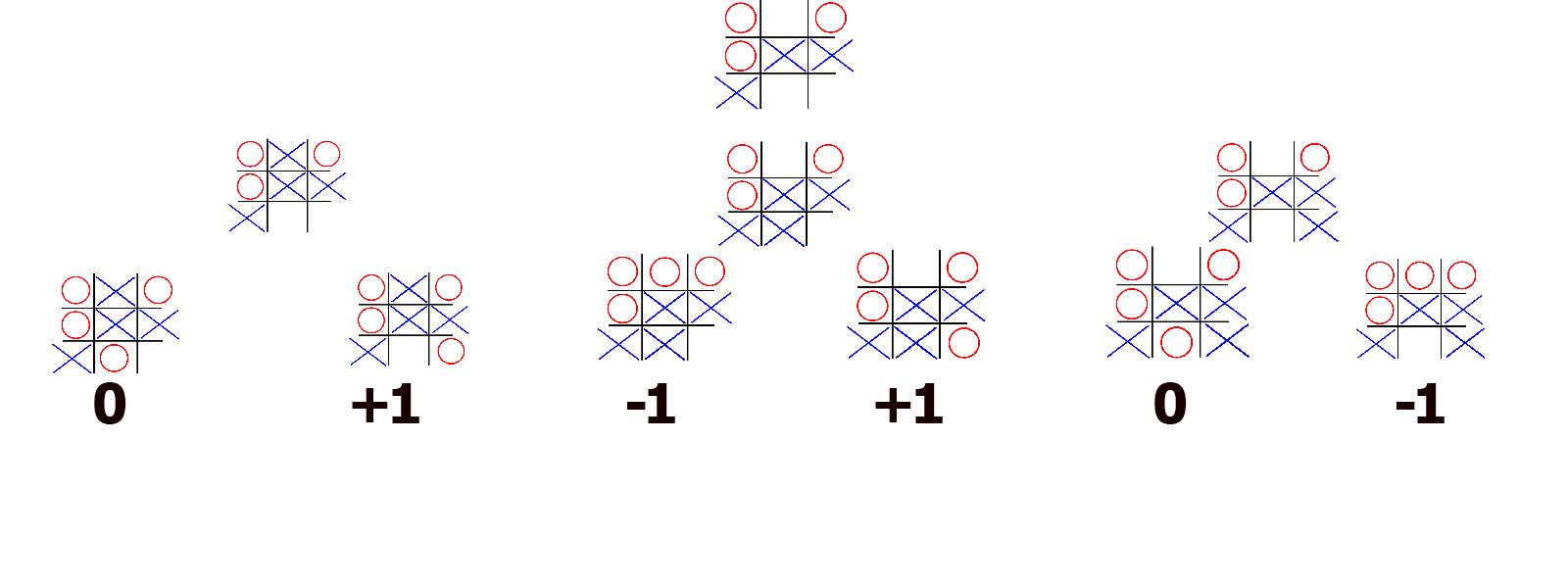

Most people who know the rules of this game, will see this position and tell you it is a draw. Great, but how do you know that? Well, unless you have seen this position before and you have memorised the outcome, you will mentally play out all possible moves and see the outcome of each. People back in 1885 had already written out an algorithm, or a sequence of steps, which when followed will help you analyse any game, without needing to know game-specific knowledge. Backwards induction works as follows. As we can see from the number of Xs and Os, it is player X’s turns. Now they can cross any of these three boxes, each resulting in a different board state. Lets see how the game would progress if they play in the top square.

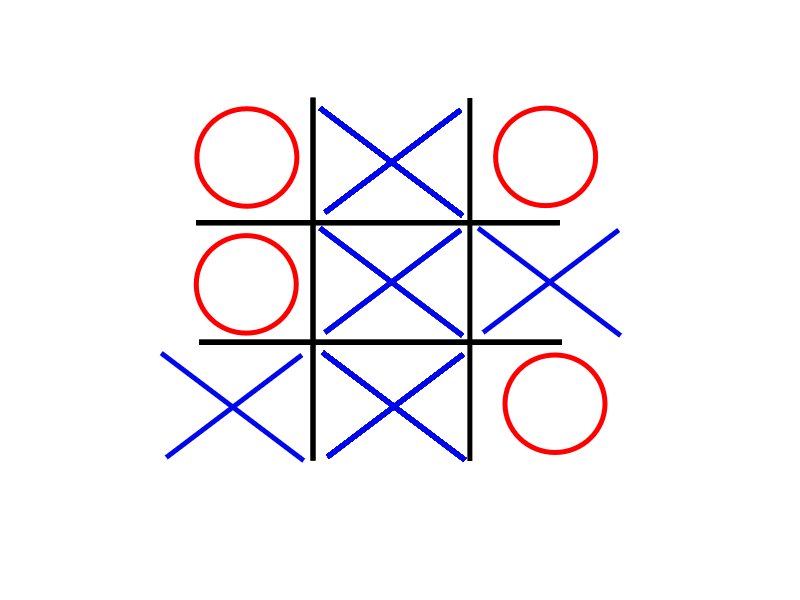

Well on the other player’s turn they can make a choice between either of the two bottom boxes. Whatever they play, X can respond with only one move. As we see if O responded by playing in the bottom right, X would win. Thus we denote the outcome of this sequence of moves as +1 (for X’s victory).

For O’s other choice, the game would end in a draw, so we put down a 0.

If player 2 (or O) had won, by convention we would put -1. We do the same for all initial choices and we end up with our complete game tree.

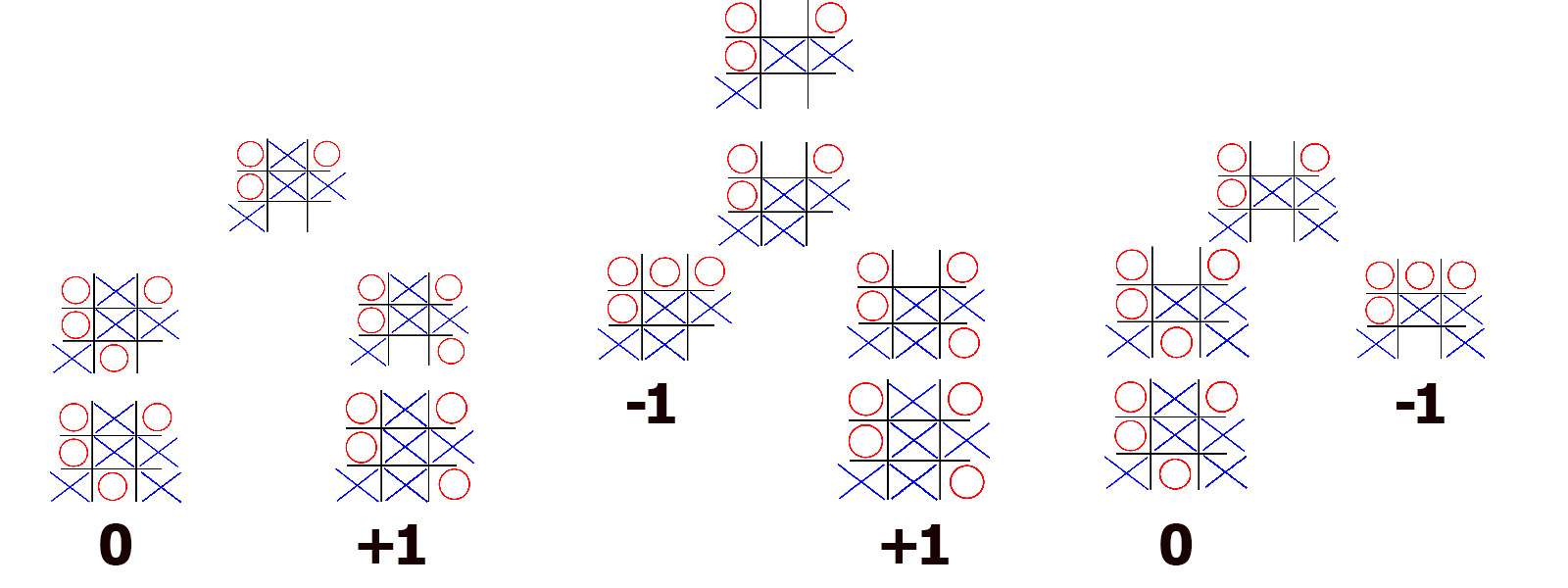

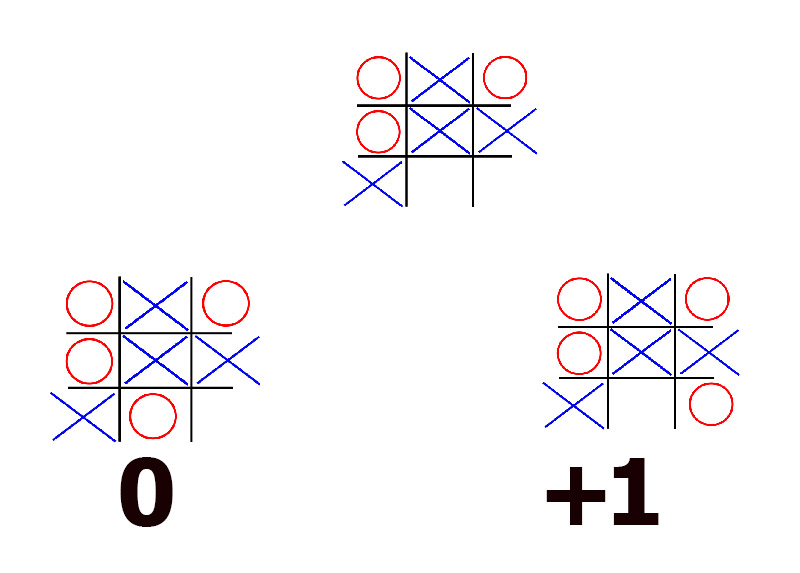

The nodes represent the different possible board configurations, while the edges or the lines represent the current player’s possible moves given that state. We now begin evaluating the tree backwards. Since player X’s last move is forced, we can simply transfer the scores of the final positions to their predecessors, as neither player can change the outcome (there is only one possible move).

Now we have all the possible second-to-last positions which O can achieve after our turn. We assume O wants to win (or at best draw) if they can. And we assume that O understands fully the principles of the game. Therefore, given Os possible choices here they would like to make a choice that would lead them to a board whose outcome is -1. If that is not possible, then 0 for draw can work, and if nothing else - well +1 they will be forced to accept. Thus player 2 is trying to minimise the outcome (trying to pick the board with minimal value). So given this board for example, they have a choice between either getting a draw, or losing. For them it would be better to draw, so the drawing move they would pick.

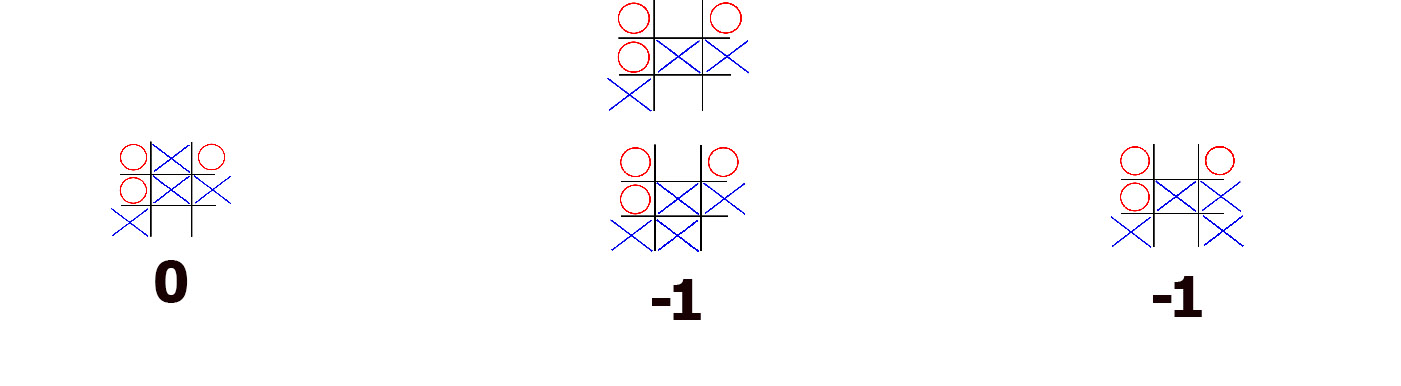

We do this all other configurations where it is player 2’s turn. Now player 1 has a choice between 3 moves. Assuming that his opponent will not make mistakes on their turn, the choices are draw, lose, or lose. Player 1 doesn’t want to lose, so they will pick the next best thing - a draw. Player 1 is trying to maximise. And hence the name of the algorithm. Minimax. One player tries to get the outcome as high as possible, while the other one - low as possible.

And that is the algorithm. That is how most chess engines work. It is a pretty intuitive algorithm, fortunately. Most of the times humans evaluate their choices in such games in much the same manner, though maybe not as consciously. The main strength of this algorithm is that you don’t need to know the previous moves. It doesn’t matter whether this position was reached like this or in some other manner like this. What matters is the current possible outcomes, since they will be the same regardless of the path we took to get here.

Stopping Early

This is great and all, but how does it apply to chess?? I mean tic-tac-toe is a simple game, even children can evaluate it fully from a starting position and know it will be a draw. It has only about a 1000 game positions. Chess on the other hand has 10^123 possible positions. The number of atoms in the observable universe is 10^82. The difference between the two is unfathomably large. If for every chess position you had an atom you could make 10^41 universes. That is 1 with 41 zeros after it. A number so large, that if I wanted to count to it, it would take me 10^33 years to do so. Our universe has existed for some mere 10^10 years. There are too many positions for any computer to consider, let alone any human. So how do chess engines do it?

Well… They cheat.. Kinda. What they normally do is evaluate 6, 10, or some number of moves ahead and then they stop. And if you end on a position where there is no winner or loser yet (terminal position), how can you tell what the outcome will be? You estimate. Or if you want to be proper, you apply a heuristic. You look at the current position and do some observations, which then give you some advantage score for one of the two players. This is actually how humans operate too. Grandmasters thin 10-18 moves ahead (depending on the complexity of the position) and then decide which future position looks best to them.

Of course the art is in finding a good way to estimate the position. The better and more detailed your evaluation is, the better your moves will be. For example you can calculate material advantage. But that is not necessarily fully informative. In chess you can sack a piece to open up the king, or get better piece development. And saying these possible ways of evaluation is easy, but translating it in a structured manner so that a computer can understand them? Not so trivial. The main focus of modern chess engines is in optimisations and designing good heuristics.

A Concrete Example

To see the algorithm in action we provide a Connect Four artificial agent which you can play against. Why Connect Four? It is a game very similar to chess, with the addition that it is SOLVED. A game is considered to be solved if we have built the entire tree from start to all possible conclusions. This allows us to do the old backwards propagation algorithm to then determine the optimal strategy for each player, that is if they do not make mistakes and want to win. For example, consider tic tac toe. Everyone knows that the game will always result in a draw, if neither party makes a mistake. I mean you probably stopped playing it at some point precisely because of how boring it got after that realisation. Connect four is also a solved game. We know that if both players play perfectly, No matter what player 2 does, player 1 will win. This makes building this toy solver much easier since we can evaluate how close to optimal it is. And since connect four is of the same class (two-players taking turns with the whole knowledge of the board) as chess, everything we do here, can easily be done for chess.

Our bot works by using minimax. It plays all possible positions some number of moves ahead (adjustable by the difficulty slider - the higher the difficulty, the more informed its moves will be, but the slower it will think). If the position is not a terminal one, it employs the following heuristic (we look at each disck separately on the board):

-

If player 1's disk is in the middle column, we add 7 to the evaluation. If it is a player 2 disk we will subtract 7 (this goes for the entire heuristic. For player 1 disks we add, for player 2 we subtract, since it is a 0 sum game).

- If it is in the columns next to the middle one, we will add 3 (subtract 3 for player 2 disk)

- If it is in the next two columns we add 1

- For the last two columns we add 0.

- If we have connected 3 disks of the same colour in a row, column, or diagonal and on both sides there are empty spaces, we add 1000.

- If we have connected 3 disks of the same colour with empty space only on one side, we add 33.

- If it is 2 connected with both sides open, we add 5.

- If four diks are connected we add infinity (or subtract for player 2).

The numbers are largely arbitrary. I am sure if you wanted you could find a better heuristic. We do this for each disc on the board. This gives us a final score for the board. The lower it is the better it is for player 2, and the higher it is - the better for player 1.

Going Deeper

We are not over yet tho. It is 2023 and of course everything has do be done with deep learning. Since 2020, every major chess engine uses a deep neural network to evaluate their positions. Why make a heuristic, when you can let the computer figure out one for you.

Here we have done the same. We trained a simple network following a convolutional structure - upsapling 2D-Convolution, Relu, and Max-pooling (only on first convolution). A residual connection exists for the last convolution. At the end, 2 linear layers with TanH activation are appended which produce 3 probabilities that player 2 wins (-1), it is a tie (0), and player 1 wins (1). The agent then uses this evaluation to pick the path which will reduce in its most probable win. The training data is available here

The code for both agents is available for both Python and JavaScript. You can interact with them below: